“You really need to attend this weekend seminar.”

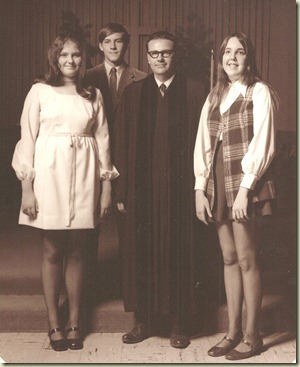

Larry and Sherry Brown were two of my students at Cotner. I had introduced them. Sherry was an attractive, petite, black-haired girl from a family in one of the churches I had served on weekends. Larry was a handsome, well-tanned product of the western Nebraska sand hills who was planning on attending seminary. I and Fran Houchen, another young radical who had been Larry’s pastor and was now on the staff of a large church in Lincoln, co-officiated at Larry and Sherry’s marriage service. The two of them had just returned from a weekend in Chicago at the Ecumenical Institute’s campus in the west-side ghetto, the very neighborhood where I had taken my Peoria high school group two years earlier.

The Institute (EI as it became known to many, sometimes articulated admiringly and by some in a derogatory manner) was attracting students from all around the country to weekend seminars called Religious Studies I (RS-1 as it became known). EI, part of the church renewal efforts of the sixties, was led by Joe Mathews who I had encountered while on the university campus, and a group of radical young clergy and laymen who had been exploring living in community while teaching and practicing a theology of the church taking responsibility for the community in deep and transformative ways. It was, you might say, the left wing of the church renewal movement.

I was searching for a way to make my spiritual inclinations relevant to the real world. I had learned as much from my students as from any of my teachers. So in November of 1967 I found myself, along with about 20 other pastors and a few lay people, in a church basement in Lincoln, Nebraska being re-introduced to Kierkegaard, Bultmann, Tillich, Bonhoeffer and H.R. Niebuhr in a way I had not dreamed. David McClesky, a tall, lanky Texan, one of 2 “pedagogues” (i.e., teachers—EI had a way of re-interpreting the old words and giving them new images) from Chicago introduced himself with: “I’m a Baptist, and not only am I a Baptist but I’m a Southern Baptist and you can’t get more Baptist than that.” George Holcombe, the other of the pair, who reminded me of a young Scrooge, began his opening lecture on G-O-D (they wouldn’t actually say the word God without spelling it out, at least in the beginning of the course) with this statement: “I’m a radical, fanatical churchman of the 20th century.” He was actually a Methodist minister and McClesky was, I later discovered, a recovering Southern Baptist. I was intrigued enough to stay for the entire 3 days of my mind being assaulted with radical-sounding theological statements, some of which began to make sense in my world, although my intellectual ego had difficulty admitting it.

We began the course by studying a paper by Rudolf Bultmann called The Crisis of Faith, followed by what I now believe was Paul Tillich’s greatest sermon ever, You Are Accepted

You are accepted; accepted by that which is greater than you, and the name of which you do not know. Do not ask for the name now. Perhaps you will learn it later.

It was that seminar on that sermon that opened me to see the heart of the Christian Gospel, without all the theological clap-trap that usually smothers the experience of grace and throws us back into our own self-made justifications and judgments of ourselves, others and the world. Before bedtime on the second evening and after a discussion of Pablo Picasso’s painting Guernica, a massive anguished response to Hitler’s saturation bombing of the Spanish town prior to World War II, we watched the classic film Requiem for a Heavyweight, the one with Anthony Quinn, Mickey Rooney, and Jackie Gleason, and discussed its theological implications. All of this was designed to force us to confront our own world views and beliefs and images of God, Jesus, and the doctrines we had been mouthing without ever grounding them in our actual experience of the way life is.

It began to dawn on me that what we were being exposed to was a method of teaching that stripped away old worn-out expressions of concepts that were becoming virtually meaningless through taking their meanings for granted, then re-investing them with meaning from our own experience of life. We were being taken through a journey of de-mythologizing and then inventing new myths (stories) more relevant in a 20th century context. By the time we had been dragged through studies of Bonhoeffer’s paper on “Freedom” from his book on ethics, and H.R. Niebuhr’s “Church as Social Pioneer” I was almost theologically and emotionally exhausted, besides being so physically drained from 2 late nights and just plain rigorous intellectual work. What was I going to do with this now? How was I going to take my little congregation through the veil I had just gone through?

Then came the altar call. The closing meal at which we were each asked for a response to the three days and what we were going to take away. I mumbled something about how I hadn’t really learned anything new from this course (my ego trying to convince everyone that I knew things but actually trying to hide my ignorance). Dave McClesky just quietly nodded, accepting my comment and said simply: “Well then, maybe it’s just a case of how you are going to be responsible for your colleagues and your parishioners.”

I was finished and I didn’t know it. The next chapter will be about the unfolding of the response.