“If you go to India your life will never be the same.” Our colleagues in the Institute of Cultural Affairs (ICA) who were assigned there always repeated the same mantra. Linda and I did not have the opportunity for an overseas assignment while on the ICA staff. Our good fortune. Just at the time of our departure from FOOD FOR ALL, our friends Roger and Maxine Butcher were organizing a “self-tour” to be led by an Indian ICA colleague, Shakuntala Jadhav, who lived in Puna. We signed on right away. A group of ten of us spent two weeks, over Christmas and New Year, 1997-8, traveling in the state of Maharashtra, and ending up in New Delhi. The Butchers had worked in India with the ICA for several years. Our longtime FOOD FOR ALL volunteer and now Board member, Helen Anderson and her husband Gordon, joined our group, along with another ICA colleague, Sara Munshin. Roger’s 80 year young mother made the trip as well, along with other assorted friends and relatives, all recruited by the Butchers.

Shakuntala met us at the Mumbai airport a little before midnight. Our first encounter with India was seeing security guards with military rifles slung across their shoulders, standing around chatting and smoking in the nearly deserted Mumbai airport terminal. Our next sight, was more pleasant. Shakuntala showed up with an aging but reliable fifteen passenger bus with a driver and “spotter.” We were to learn how important the role of spotter is over the next two weeks. The Butchers told us they had put our group in the hands of this young, attractive, powerhouse of a woman in a sari; and we could rest easy that all would be well-organized. We had made her acquaintance two years earlier when she came to the US and stayed with us for a night while on a fundraising trip. FOOD FOR ALL was a supporter of a village project she and her husband Shankar headed up, as well as a new environmental training center that was well under construction. We were to visit both in the next few days.

We drove at night to get to our hotel through the “suburbs” of Mumbai, barely making out the vastness of the slum neighborhoods, with occasional single electric lights visible among the many cooking fires. We could see figures of what we realized were families gathered for a “midnight snack,” possibly the only meal of the day after and before a day of scratching out a living. The experience was surreal. Out of the darkness came suddenly a brightly lit open truck with music blaring and a crowd of people following and singing. It was a wedding celebration.

After an hour of driving on a two-lane highway, with the smells of gasoline fumes mixed with charcoal, various scents of foods cooking, garbage rotting alongside the road, occasional animal waste and open sewage, we arrived at our first night’s lodging in the little town of Punvel, and were warmly welcomed by two staff of the Punvel Palace, one of our many “minus one-star” hotels. We had not yet seen Slum Dog Millionaire or Best Exotic Marigold Hotel so had nothing to compare. The rooms were clean and we were exhausted. So we slept. We woke with the residents of Punvel already at work with the sunrise. Our hotel room overlooked a small lumber yard. The view of workmen, trucks being loaded, and cows meandering was strange but seemed to totally fit the scene.

Taking a shower in India is an interesting experience. The bathroom does not contain a shower. The bathroom is the shower. And if the hotel staff are on the ball and stoke the boiler, you might get hot water. To our surprise, the hotel staff had breakfast prepared for us. Our expectations were not exceeded. An over-cooked egg and toast and some kind of fruit. And a bottle of water or a sugary orange drink. But we were hungry so we ate.

Shakuntala was ready for us. The plan was to spend the first week visiting ICA projects in the State of Maharashtra, and the second week as tourists. We thanked the Punvel Palace staff, boarded our little bus, and drove back to Mumbai so we could see what we had only sensed on the trip from the airport. We had a view of slum neighborhoods as far as we could see. Mumbai is a vast sea of people, animals, trucks (called Goods Carriers), three-wheeled motorized vehicles used for taxis, and for transporting anything and everything, all constantly moving. Everyone in India seems to be on the way somewhere. The only time we saw people who might be taking a break from their incessant activity was late at night around the cooking pots.

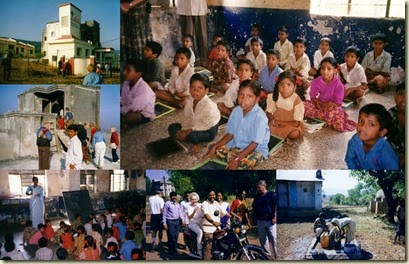

On the way back to our hotel we stopped at a nearby project in the little town of Chikhale which was run by women making clothing, then saw our first village school, one room with bare walls and children sitting on a dirt floor, after which we visited a family of an ICA staffer. Monu’s son had been in a motorcycle accident, and the Butchers had collected a sum of money to help the family during his recovery at home.

After a second night at the Punvel Palace we were on the road to Puna, the second largest city in Maharashtra where the Jadhavs lived. They managed several of the ICA projects with a small staff in some nearby villages. We were treated to a real “home-cooked” Indian dinner on Christmas day at their home, prepared and served by Shakuntala and some women friends. Since Puna is a large city, our hotel accommodations were a bit more comfortable.

The next day we were on our way to the Environmental Training Center in a town called Malegaon. The Center was nearly complete and served many of the surrounding villages as a resource for developing best practices in conservation and farming. Our next overnight was in the town of Telegaon. We were on the way to a village where we visited a residential school the ICA had started, another that the ICA helped drill a new village well, and finally one of the poorest villages where we were met by the village band (with instruments made from various sizes of metal drums), marched the two blocks to the town center, and marked on the forehead by the village women.

We sat and learned of how proud they were of the partnership they had with ICA and how they discovered the power and importance of the women of their village (in India rural society, the women do most of the hard work and the men make all the decisions). We were even invited into one of the homes for afternoon tea.

Warm memories of these few days abound. While walking on the foot path through a field to get to a village, we met a wedding procession of poor farmers who were transporting the bride to the wedding on a two-wheel bike. The family was over-joyed at our congratulations and I am sure saw this as a good omen for the marriage. On another walk through the fields, which was the only way, other than motorcycle, to get to some villages, Roger and I offered to help a couple of farmers who were threshing grain and talked another farmer into giving us a ride in his ox cart (I confess, both were mainly for photo ops).

In one village we were invited into a home, typical of most in rural India. There was no furniture, a dirt floor, well-swept. There was only one bare light bulb in the kitchen. Grandpa sleeping on a straw mat on the floor in one corner. Three women sitting and grinding corn. The family cow looking over a counter from her pen in one end of the house. In the kitchen no table or chairs, four stainless steel cups and plates on a shelf and one cooking pot on an open fire pit.

Toward the end of our first week we made a long bus drive on a public bus to the city of Aurangabad, which was near the ICA’s very first Indian village project, Maliwada. The picture you have in your minds about Indian public transportation might be accurate, but you really have to experience it. I mentioned earlier that every bus has a driver and a spotter. The driver drives and operates the horn, which is more essential than the brake. The spotter sticks his head out the window and signals the driver when he assesses that it’s safe to pass. Indian highways are unique in the world. There are people walking along the roadsides, carts pulled by camels or oxen or men, motorized scooters, taxis, bicycles. There are the many trucks, buses, a few private cars, pickups, and cows. I lost all fear in the two weeks I spent in India.

Now for the scene on the bus. People in various states of cleanliness get on and off at every bus stop. There are no smoking prohibitions on Indian buses and the sweet smell of Indian tobacco and whatever else some guys were smoking was slightly sickening, but the windows were always open so no one actually got sick on our tour. There were people carrying all sorts of things, and the body smells sitting close to fifty people added to the experience. The bathroom breaks were another scene worth telling. The driver would pull over to the side of the road by a field of grain or mustard and say “men left, women right,” while pointing. And I can testify that this was preferable to some of the public toilets in towns along the way. An eight hour bus ride I will never forget.

The overnight in Aurangabad would have been very comfortable. The hotel rooms and beds were adequate for our needs for rest. We noticed that there was no hot water for showers and mentioned this to the hotel staff. We should have kept quiet. The boiler to heat the water was outside the hotel below our room. When the fire was lit, the smoke filled the hotel and it took several hours of burning eyes to recover enough to think of taking a shower. But the water was hot.

The day following was worth it. The Ellora Caves are near Aurangabad and are a historic site of both Hindu and Buddhist temples, carved right out of the mountain. We were not prepared for the barrage of monkeys that hung around the caves; and we were surprised at how little protection the Indian government provided for its historic treasures.

The real treat of the day was the visit to the village of Maliwada. Shakuntala and her husband Shankar had been early ICA staff in this village in the 1970s. The villagers remembered her and gathered around with exuberance. We toured the village. It didn’t take that long. The one indelible image that remains with me is the dozens of children crowding around us, following us shouting and waving for attention the whole time. The mural of the mountain and the Dalatabad Fort you could see from the village was still visible on the community center building. This took me back to my ICA staff days. I always wanted to go to Maliwada. Now I was there.

After Maliwada we were ready to be tourists. Shakuntala got us back on the public bus for the trip back to Pune, another eight hour experience of Indian in-country travel, driver laying on horn, spotter calculating the inches for safe passing, wonderful mass of humanity packed together into a microcosm of spaceship earth. I must confess I loved it. On one occasion when Shakuntala and I got separated from the group for an hour or so, she pitched me for how cheap it would be for Linda and me to live on our retirement income in India. For a moment that sounded really good. This woman was very convincing. Her husband had said to us once: “She is a very powerful woman.” (Shakuntala died in 2003 of cancer).

We were now prepared for the tourist experience. The flight to Jaipur on Air India was a total surprise. We had just taken off for an hour flight when we were served a delicious, full meal. We had hardly time to enjoy it when the landing lights came on. The stay in Jaipur encompassed a visit to the “Pink Palace” of some emperor, a ride on an elephant, and our taxi driver stopping a local camel driver to allow those of us who wanted to ride his camel for a photo.

Our accommodations were fine, except we had to keep our hotel room window closed to keep the monkeys from entering during the night. Getting up early in the morning gave us the experience of seeing the city of Jaipur waking up. Monkeys heading for the roofs, cows meandering through the street to be fed by merchants. Street sweepers beginning to clean the piles of trash.

Next to experience was the Indian train ride to Agra, home of the Taj Mahal. Again, we were surprised at the modern comforts. I believe the fact that Shakuntala had arranged for us to have assigned seating had something to do with our comfort level. They actually served us a meal on the train. Hotel accommodations in Agra were a slight improvement. The early morning visit to the Taj Mahal was an inspiring experience. We got to see the sun rising over the Taj, from the island across the river to the back, due to an encounter with a “tour guide” and his boatman who wanted to take us across the river to a sandbar, promising a unique experience. So Linda, Helen Anderson and I took him up on it. It was a spectacular view. We later discovered that it was the only day in about three months that the cloud cover allowed for viewing the sunrise. Dickering on the price of the tour was fun (200 rupees? No, he meant 200 rupees each—so $10 for the three of us) and made us feel like cheapskates.

A train trip the next day landed us in New Delhi, and preparations for our trip home. Visits to the Red Fort in Old Delhi, an ancient mosque, a sound-and-light show, the Mahatma Gandhi museum, Indira Gandhi’s home, and changing hotels because Shakuntala happened to see a rat running along the hotel balcony rounded out our two week immersion in India.

Someone in our group, while wandering the neighborhood of the hotel, discovered a “pancake house” and a “21 flavors ice cream store” in the same building. We made several trips there over the three days stay.

We returned home on January 5th, 1998, exhausted but totally grateful for the India experience. India is truly a life-changing event. The contrasts of our first week of seeing the extreme poverty that is much of rural and urban Indian life, and the modern comforts of the second week’s tour were stark. It’s just that India is too much of everything. A feast of sight and sound. Too much poverty and suffering. Too many people. Too much complexity. And yet somehow it seems to work.

So what has this to do with the FOOD FOR ALL story? Linda and I had turned in our resignations. We had not yet had time to reflect on our FOOD FOR ALL journey. But as we began to piece together the fabric of our life through the past couple of decades, what was becoming clear was that we had participated in a grand experiment of what it means to be of service. If we had ever thought that we were going to change the world or save it, such thinking evaporated in India. And yet we saw with our own eyes change occurring. We heard with our own ears from people in villages stories of hope and pride in their accomplishments. We felt privileged to be even a small part of it all. We realized that it had never been about us and what we could accomplish. We were riding on waves of change that took us along with them. We were facilitators. We were the invisible presence that saw to it that when an individual, a town, a village, a group of any sort, experienced a success in any endeavor that we were a part of, they would look at the accomplishment and be able to say: “We did it ourselves.”

The few million dollars in grants that had passed from supermarket check stands through FOOD FOR ALL’s grants to self-help projects such as the ICA’s village development projects were just part of the human community’s struggle to say to itself: “Life is good! The future is open!”

It is good to be a part of something like that. Who could ask for anything more?

In the words of a poem by D.H. Lawrence:

Not I, not I, but the wind that blows through me!

A fine wind is blowing the new direction of Time.

If only I let it bear me, carry me, if only it carry me!

If only I am sensitive, subtle, oh, delicate, a winged gift!

If only, most lovely of all, I yield myself and am borrowed

By the fine, fine wind that takes its course through the chaos

of the world

Like a fine, an exquisite chisel, a wedge-blade inserted;

If only I am keen and hard like the sheer tip of a wedge

Driven by invisible blows,

The rock will split, we shall come at the wonder, we shall

find the Hesperides.

No comments:

Post a Comment